An Opinionated Tutorial on ROS Node Design

Fluency with ROS is essential for doing robotics. A lot of the students I’ve worked with in the past have no problem getting through the ROS tutorials, but start to flounder as soon as they need to create their first ROS node. My goal with this tutorial is to introduce a few techniques that make writing ROS nodes easier. I’m going to assume that you’ve installed ROS Kinetic on an Ubuntu system, and have at least looked at the beginner ROS tutorials. Also, since C++ is primary language for doing robotics at the moment, this tutorial is focused on C++ development. I’ll cover the following topics to give you a template for developing your own nodes:

- Working with bag files

- Using classes to represent ROS nodes.

- Working with configuration files

- ROS timers

To show these concepts in action, the example robot we’re going to use is my team’s Lincoln MKZ:

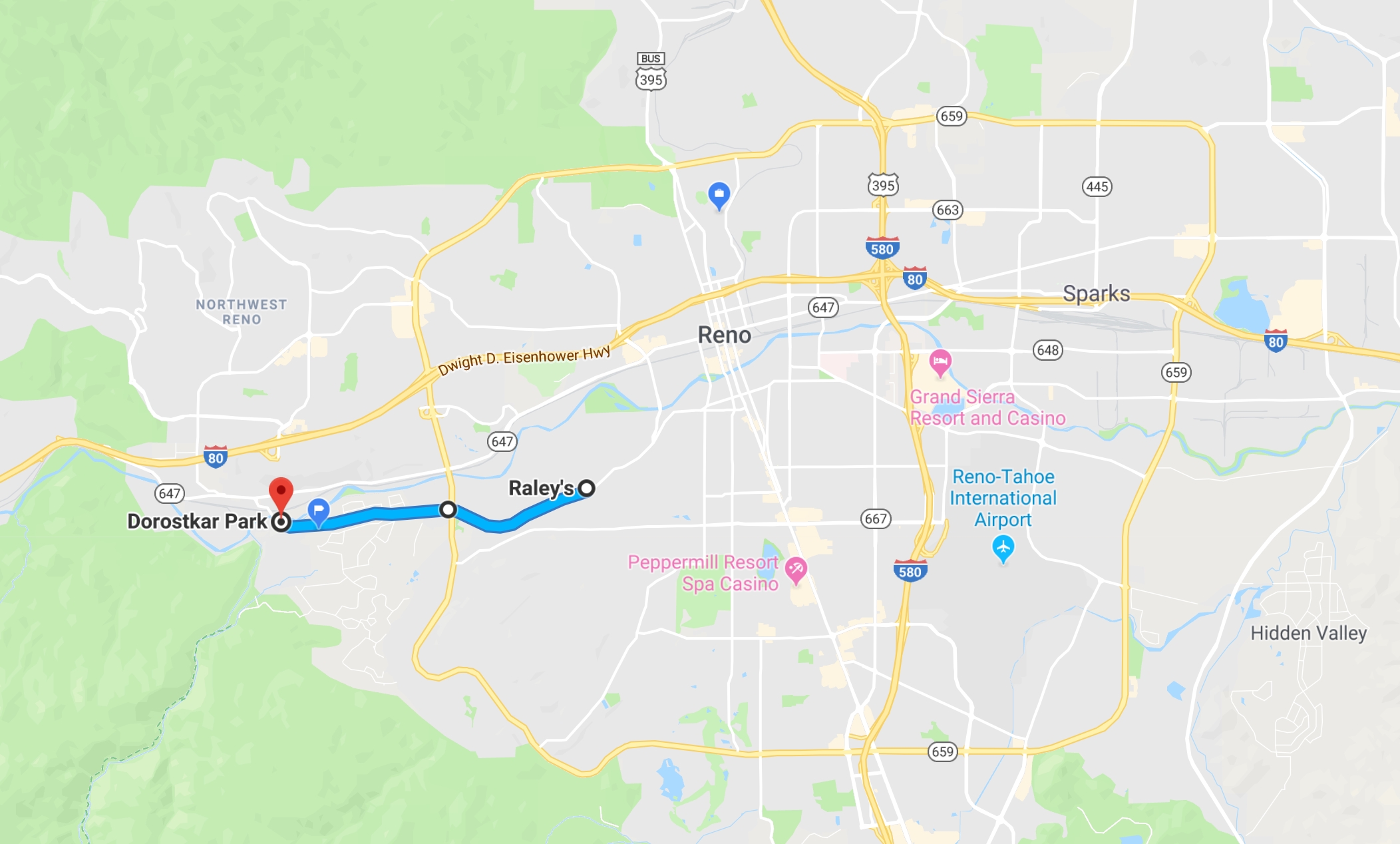

The ROS node we will look at computes the total distance traveled by my team’s car as it travels along Mayberry Drive in Reno, Nevada:

The car has a GNSS system that gives us position and velocity information at a relatively high frequency (100 Hz), and we’re going to integrate that information along the path the car travels to get the total distance traveled. This is a toy problem, but still useful enough to be interesting; we use a similar node to keep track of how many miles our car has driven autonomously.

Getting Started: Data and Code

You should be able to run all of the code in this tutorial. To do so, you’re going to need to download two ROS packages and one bagfile containing a recording of the car’s trip.

Getting the bagfile

One very cool feature of ROS is that it allows you to record

bagfiles while you run your robot. This is essentially a recording

of all the messages sent and received on your robot as long as the

rosbag recorder is running. You should get into the habit of recording

bagfiles as often as possible, because they are essential for

debugging and development. I drove our car along Mayberry in manual

mode and recorded the GNSS data, the vehicle data, and the data from

one of our Velodyne VLP-16 lidar units using rosbag record. The

result is a file named 2018-09-05-21-12-15.bag. Because of the lidar

data, this bagfile is large - about 11GB. Keep that in mind before

downloading the file at this link:

Once you have this file, you can run the following two commands (in

separate terminals) to play back the recorded trip (the $ indicates

a new terminal prompt):

$ roscore

$ rosbag play -l --pause 2018-09-05-21-12-15.bag

A few things to note here:

The -l option causes playback to loop once the end of the file is

reached. The --pause option causes the playback to start in a

paused state. You can then either step through playback by repeatedly

hitting s or you can start normal playback by hitting the space bar.

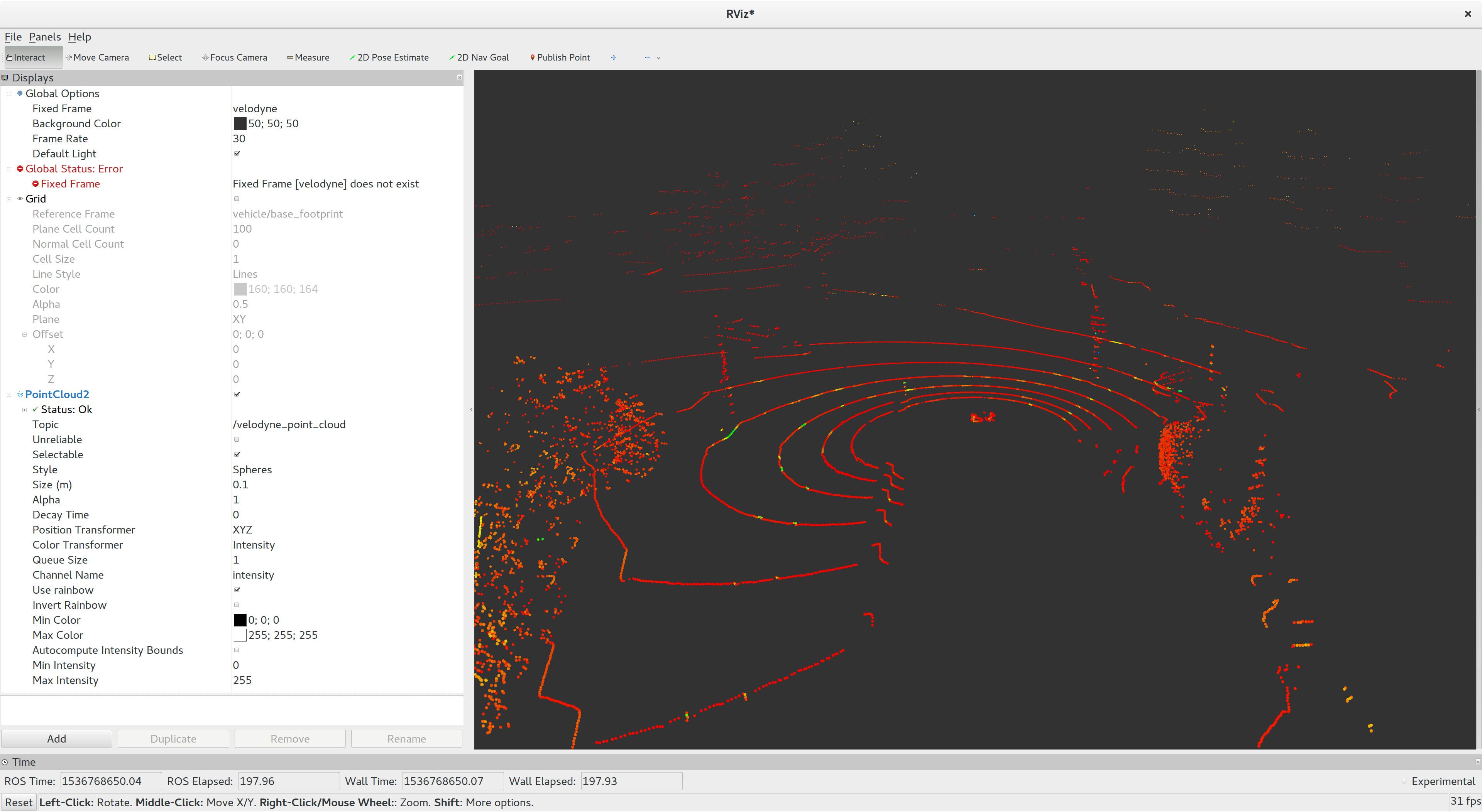

Once you’ve started playing back the file, you can open rviz and see

the point cloud:

$ rosrun rviz rviz

Add a new display by topic, add the appropriate point cloud topic, and

change the fixed frame to velodyne and you should see the point

cloud:

Try copying the settings on the left if you’re having trouble getting the cloud to show up. Once you’re able to visualize this cloud, you’re ready to download the two packages we need to start looking at code.

Getting the packages

Before you download the packages, you need to create a catkin workspace. If you’ve gone through the ROS tutorials, you’ve done this already. Just so we’re on the same page, here are the commands I ran on my machine to generate a workspace:

$ mkdir tutorial0_ws

$ cd tutorial0_ws

$ mkdir src

$ cd src

$ catkin_init_workspace

$ cd ..

$ catkin_make

The last command, catkin_make, isn’t strictly necessary, but is

useful for catching system configuration problems. In particular, I

use anaconda to manage my Python workflows for machine learning. ROS

assumes that you’re running the Ubuntu system Python, so I usually

disable anaconda’s Python before starting to work on ROS (this is a

huge pain, and if you have solved this problem I would love to know

how). Running catkin_make on an empty workspace is a quick way to

isolate the “wrong version of python” problem when starting a new

project like this.

Once catkin_make runs without error, you’ll want to put two packages

into the src directory of your workspace. The first package you’re

going to need is my ROS port of Baidu’s Novatel driver:

This is necessary to be able to read the messages that our GNSS system produces. We only need the message definitions here; we don’t really care about the driver code for this tutorial.

The second package we need is the tutorial code itself:

This is the package whose code we’ll look at. To get these packages,

the commands to run (within src) are:

$ git clone https://www.github.com/richardkelley/gnss_driver.git

$ git clone https://www.github.com/richardkelley/odom_integrator.git

Once these commands are done, you can build the workspace. Assuming

you’re still in src, you should run the following:

$ cd ..

$ catkin_make

This should build both packages in the correct order. To be able to

run the odom_integrator node you’ll need to source the workspace’s

setup.bash file. To do so, make sure you’re in tutorial0_ws and run

$ source devel/setup.bash

(Remember that whenever you open a new terminal to work with

odom_integrator, you’ll need to run this command.) Once the code is

building and you’ve sourced the workspace’s setup.bash file, you can

see the node in action by opening a new terminal and running

$ rosrun odom_integrator odom_integrator_node

Once that’s running, in a new terminal run the following command:

$ rostopic echo -c /odom_integrator/distance

The -c option clears the screen each time a new message is received,

rather than just scrolling and making a mess of your terminal. You

should see the distance traveled incrementing in your terminal. If you

compare this number with the motion of the point cloud in Rviz, you’ll

see that the number changes faster or slower as the car speeds up and

slows down - a good sanity check on the system’s behavior. If you run

rosbag play without the -l command, you should see that the car

travels approximately 4.6 kilometers from the start of the recording

to the end.

Now that you have the

odom_integrator_node running, it’s time to look at the code that’s

computing the distance traveled.

The odom_integrator Package

To understand how odom_integrator produces that number, we’re going

to walk through the code in that package. Start by running the tree

command (you may need to run sudo apt install tree to install this):

$ roscd odom_integrator

$ tree .

The tree command should produce output that looks like this:

.

├── CMakeLists.txt

├── conf

│ └── conf.yaml

├── include

│ └── odom_integrator

│ └── odom_integrator.h

├── package.xml

└── src

├── odom_integrator.cpp

└── odom_integrator_node.cpp

4 directories, 6 files

We’ll start by looking at the main function, in

src/odom_integrator_node.cpp. This is a short file, but there are

two interesting things going on in it. First, we’re using

ros/package.h to get the path to a configuration file in a portable

way. Second, we’re going to use a class to contain the state and

callbacks of our ROS node.

Working with paths in ROS

Working with directories in ROS is actually pretty easy. You need one

#include and one function call. The #include is on line 13 of

odom_integrator_node.cpp:

#include <ros/package.h>

and the function call is on line 25:

std::string path = ros::package::getPath("odom_integrator");

The result is that the variable path holds the path to the package

odom_integrator (in this case, the current package). Because ROS

tries hard to separate itself from Ubuntu’s directory structure, this

function is probably the only way to make sure your code works without

recompiling across multiple machines. Once we have the path to the

package, we can specify the full path of the configuration file we’ll use:

std::string full_path = path + "/conf/conf.yaml";

We then pass this full path into the constructor for our node class.

Using classes to represent ROS nodes

Looking at main, you probably noticed that it contains none of the

“usual” declarations you expect in ROS: there’s no NodeHandle, there

are no Publisher or Subscriber objects, etc. That’s because the

proper way to manage those objects in C++ is via a class. Look at

the end of main:

odom_integrator::OdomIntegratorNode node{full_path};

ros::spin();

Here, we pass full_path into the constructor of an

OdomIntegratorNode, and then let ROS go. It doesn’t look like node

is doing any work here, but because we declare our callbacks and

publishers as member functions of OdomIntegratorNode, all we need to

do is create our node object, initialize the ROS-relevant objects in

the constructor, and let the process go. This allows your callbacks to

share data without the use of unnecessary global variables, and also

uses the C++ idiom of RAII (“Resource Acquisition is

Initialization”)

to ensure that any resources you acquire will be cleaned up when the

object representing the node is cleaned up. That doesn’t really matter

in a node as simple as this one, but in complex ROS nodes that manage

resources (and in general C++ programming) this is an approach you

should probably almost always use.

To see how we structure our class, let’s look at odom_integrator.h

in include/odom_integrator. First, note the use of the namespace

odom_integrator wrapping our class. Namespaces prevent name

collisions, and as you write more complicated systems based on ROS,

you should use namespaces like this to ensure that these conflicts

don’t occur.

Here’s the full class:

class OdomIntegratorNode {

public:

OdomIntegratorNode(const std::string& filename);

void gnss_callback(const gnss_driver::GpsConstPtr& gps_msg);

void timer_callback(const ros::TimerEvent& event);

private:

bool load_configuration(std::string filename);

ros::NodeHandle nh_;

ros::Subscriber gnss_odom_sub_;

ros::Publisher distance_traveled_pub_;

ros::Timer distance_traveled_timer_;

std::string conf_filename_;

gnss_driver::Gps last_odom_;

bool use_position_ = false;

bool first_ = true;

double distance_traveled_ = 0.0;

};

We make the constructor and our two ROS callbacks public member

functions, and we make our NodeHandle and our ros::Publisher,

ros::Subscriber, and ros::Timer private member variables. We then

initialize these variables in the class’s sole constructor. Opening

src/odom_integrator.cpp, you can see how this works:

OdomIntegratorNode::OdomIntegratorNode(const std::string& filename)

: conf_filename_{filename} {

gnss_odom_sub_ = nh_.subscribe<gnss_driver::Gps>("/gnss_driver/odometry", 1,

&OdomIntegratorNode::gnss_callback,

this);

distance_traveled_pub_ = nh_.advertise<std_msgs::Float64>("/odom_integrator/distance", 10);

distance_traveled_timer_ = nh_.createTimer(ros::Duration(0.1),

&OdomIntegratorNode::timer_callback,

this);

load_configuration(filename);

}

If you’ve worked with publishers and subscribers in ROS before, the

only thing that may stand out as unusual here is the list of arguments

we pass to subscribe. Because our callback

(OdomIntegratorNode::gnss_callback) is a member function, we have to

pass both a pointer to the function (the third argument) and a pointer

to the object whose member function we want to call (the pointer

this).

We follow the same pattern in createTimer. If you haven’t seen ROS

timers before, it’s worth taking a look at this function call and the

corresponding OdomIntegratorNode::timer_callback. Timers behave like

subscribers, except that they receive ros::TimerEvent objects on a

regular schedule specified by the first argument to createTimer. In

this case, we’re going to call OdomIntegratorNode::timer_callback at

10 Hz. Timers are extremely useful, especially for things like

planning and control loops that need to run at a set frequency.

The actual callbacks are the same here as you would write them in the style of the official tutorials. Once you have the skeleton of your program in place using a class to organize everything, all you have to do is write the code to solve robotics, or whatever ;)

ROS and YAML

The last line of the OdomIntegratorNode constructor is a call to

load_configuration. Let’s look at the body of that function:

bool OdomIntegratorNode::load_configuration(std::string filename) {

std::cerr << "Loading configuration: " << filename << std::endl;

YAML::Node c = YAML::LoadFile(filename);

if (c.Type() != YAML::NodeType::Map) {

ROS_ERROR("Invalid configuration.");

return false;

}

if (c["odom_type"].as<std::string>() == "pos") {

ROS_INFO("Using position-based odometry.");

use_position_ = true;

} else if (c["odom_type"].as<std::string>() == "vel") {

ROS_INFO("Using velocity-based odometry.");

use_position_ = false;

} else {

ROS_ERROR("Unknown odometry type requested.");

return false;

}

}

We are going to give users of our node two ways to compute the

distance traveled (this is a bit artificial, but shows off YAML usage

in a mildly interesting way). The first option will be to look at the

consecutive position estimates returned by GNSS, compute the distance

between these estimates, and add all of the increments. The second

option will be to use the velocity estimates (also returned by

GNSS). We’ll get the time difference dt between consecutive

estimates (which will be small, because the GNSS driver runs at 100

Hz), multiply that dt by the norm of the velocity vector, and add up

the result over time, essentially approximating the integral

definition of arc

length. Rather

than force users to recompile the node to switch between these

computations, we’ll use a YAML file. YAML is the “preferred” ROS

method for specifying configuration information, and is (almost) built

into ROS itself. Let’s look at the file conf/conf.yaml:

---

odom_type: pos

This is a single pair that specifies that the key odom_type maps to

the value pos. Looking at load_configuration above you can see

that there are two valid options: pos and vel. Changing between

these two values in conf.yaml will cause use_position_ to change

between true and false, which will in turn cause

OdomIntegratorNode::gnss_callback to switch between the two distance

computations described above. Incidentally, this function also shows

the two ways to print information to the terminal in ROS nodes

(namely, using std::cerr and the ROS_INFO-style printing

functions).

CMake Gotchas

As I mentioned above, ROS uses YAML for most of its internal

configuration, and YAML is almost built into ROS. You’ll notice in

odom_integrator.cpp that we used the following #include to get

access to YAML:

#include <yaml-cpp/yaml.h>

We don’t have to do anything special to be able to reference this

header, but if you don’t explicitly link to the YAML libraries, your

node won’t compile. In CMakeLists.txt, you need to specify that

linking as follows:

target_link_libraries(${PROJECT_NAME}_node

${catkin_LIBRARIES}

yaml-cpp

)

That yaml-cpp is necessary. This is an annoying extra step, but such

is life.

While we’re on the topic of CMake, it’s also probably a good

idea to get in the habit of including the following line in your

CMakeLists.txt:

add_compile_options(-std=c++14)

When you create a new ROS node, a similar line appears in the file by

default (-std=c++11 instead of -std=c++14), but is commented

out. Unless you have an extremely good reason to do otherwise, you

should uncomment the line and change the 11 to a 14. This won’t break

your builds, and it will give you access to modern C++, which you

really should be using. Advantages of C++14 over C++11 are: better

type inference, more powerful lambdas, and the C++ folks finally

remembered to put make_unique into the standard library.

Conclusion

Robotics programming with ROS can be hard, but you can develop habits to make it easier. Hopefully this tutorial is enough to get you started writing your own ROS nodes in modern C++, which will let you focus more on the robotics problems you’re trying to solve instead of contemplating proper ROS design. Most of the items we covered here are a good idea to include in your own development. Even if you don’t write your nodes this way, the patterns are common enough that you’ll probably encounter them reading other people’s code.

The odom_integrator package is only a few hundred lines of code, but

this tutorial didn’t go over every line that makes up the node. Dig

through the code on Github, run it yourself, and play around until

you’re comfortable making use of these ideas in your own work.

I would love your help making this post better. If you have questions or suggestions, please send them my way.